FROM PLAYER TO LEADER: LESSONS I’VE LEARNT BEING IN GLOBALFASTFIT

Meshack Simiyu , Kenya Feb 13, 2026

From Player to Leader: Lessons I’ve Learnt Being in Global Fast Fit

There was a time when everything was about me.

My training.

My fitness.

My matches.

My performance.

I measured progress by medals, speed, strength, and applause. If I played well, it was a good day. If I didn’t, it wasn’t.

But leadership changed the scoreboard.When I became more involved in Global Fast Fit (GFF) — organizing sessions, planning tournaments, coordinating people — I slowly realized something: being a player develops skill, but being a leader develops character.And character is tested daily.

The Day I Realized Leadership Is Heavy

I remember events where not everything went as planned. Attendance wasn’t as high as expected. Equipment wasn’t perfectly organized. A few participants arrived late. A day when the tournament day arrived with less than two entries. As a player, I would have focused only on my match.But that day, I couldn’t.

I was thinking about logistics.

About timing.

About how people were feeling.

About what could go wrong.

I learned that leadership is mental weight. You carry the vision, the pressure, and sometimes even the disappointment — quietly.

But you also carry hope.

Performance Gets Applause. Leadership Gets Responsibility.

When you perform well as an athlete, people clap for you.When you lead, people look at you.

They look at:

-

How you respond when things fail

-

How you treat people

-

Whether you stay calm under pressure

-

Whether you are consistent

There were moments I had to encourage others even when I felt tired myself. Moments I had to stay positive when resources were limited. Moments I had to show up early and leave late.Leadership doesn’t always feel glamorous.But it feels meaningful.

Talent Is Everywhere — But Structure Is Rare

Through organizing tournaments and training sessions, I’ve seen raw talent. Strong players. Fast learners. Determined young athletes.

But I’ve also seen how many lack opportunity.That realization changed my mindset. Instead of asking, “How can I improve myself?” I started asking, “How can we build systems that help others improve?”

Leadership is about building structures:

-

Consistent training schedules

-

Clear communication

-

Organized competitions

-

Fair opportunities

A single good player wins a match.

A strong system builds generations.

Discipline Became My Anchor

There are days motivation is high — especially after success.

But the real test is showing up on ordinary days.

The quiet mornings.

The small sessions.

The days few people notice.

Building GFF taught me that discipline creates momentum. When you show up consistently, even when it’s hard, people begin to trust you.

And trust is the foundation of leadership.

Leadership Is Service, Not Status

At first, I thought leadership meant giving instructions.Now I understand it means serving first.

It means:

-

Preparing before others arrive

-

Checking on members individually

-

Solving problems without complaining

-

Taking blame when necessary

It means putting the mission above your ego.

True leadership is invisible effort.

The Biggest Shift: From “Me” to “We”

As a player, my focus was improvement.

As a leader, my focus is impact.

Seeing someone gain confidence.

Watching a beginner improve week by week.

Observing a team work together.

Those moments feel bigger than any trophy.

Because leadership multiplies success. It’s no longer about one person winning — it’s about a community growing.

I Am Still Learning

The journey from player to leader is not complete. I am still learning patience. Still learning communication. Still learning how to balance ambition with empathy.

But one thing is clear:

Leadership is not about being ahead of everyone.

It’s about lifting everyone.

And through Global Fast Fit, I have discovered that the greatest victory is not standing alone at the top — it is building something that stands even when you are not there.

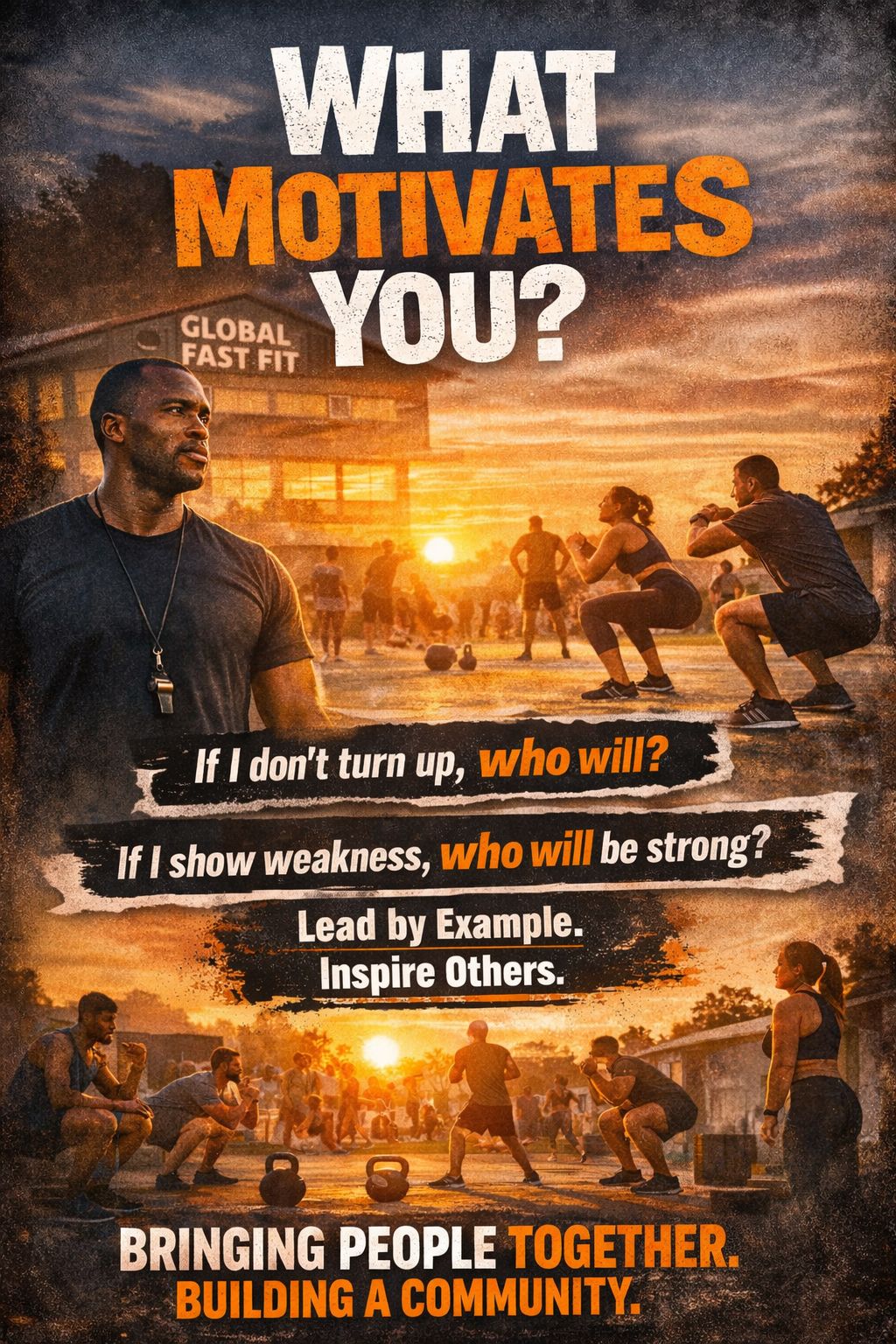

What Motivates You?

Simon Njuguna Muchiri , Kenya Jan 29, 2026

Since the opening of the GFF Center, my days have taken on a new rhythm. Waking up at 5 a.m. so I can be at the center by 5:30, ready for the morning workout, has become routine. At the beginning, it wasn’t easy. The body resisted, the mind negotiated, but deep down I knew it had to be done.

Slowly, people started showing up. One by one, then in small groups. As the numbers grew, so did my motivation. There’s something powerful about knowing others are counting on you. It pushes you beyond comfort. I often ask myself: If I don’t turn up, who will? If I show weakness, who will be strong? Leadership, I’ve learned, is not about words—it’s about showing up, especially on the hard days.

Seeing people choose to start their day with exercise is a constant reminder of why I began this journey. Their commitment fuels mine. Every stretch, every run, every shared breath at sunrise reinforces the belief that we are building something meaningful together.

So far, so good. The early mornings, the discipline, the consistency—it all feels worth it. My motivation comes from the people, from the community we’re growing, and from the simple act of showing up. And as long as there are more people to inspire and bring on board, I’ll keep pushing.

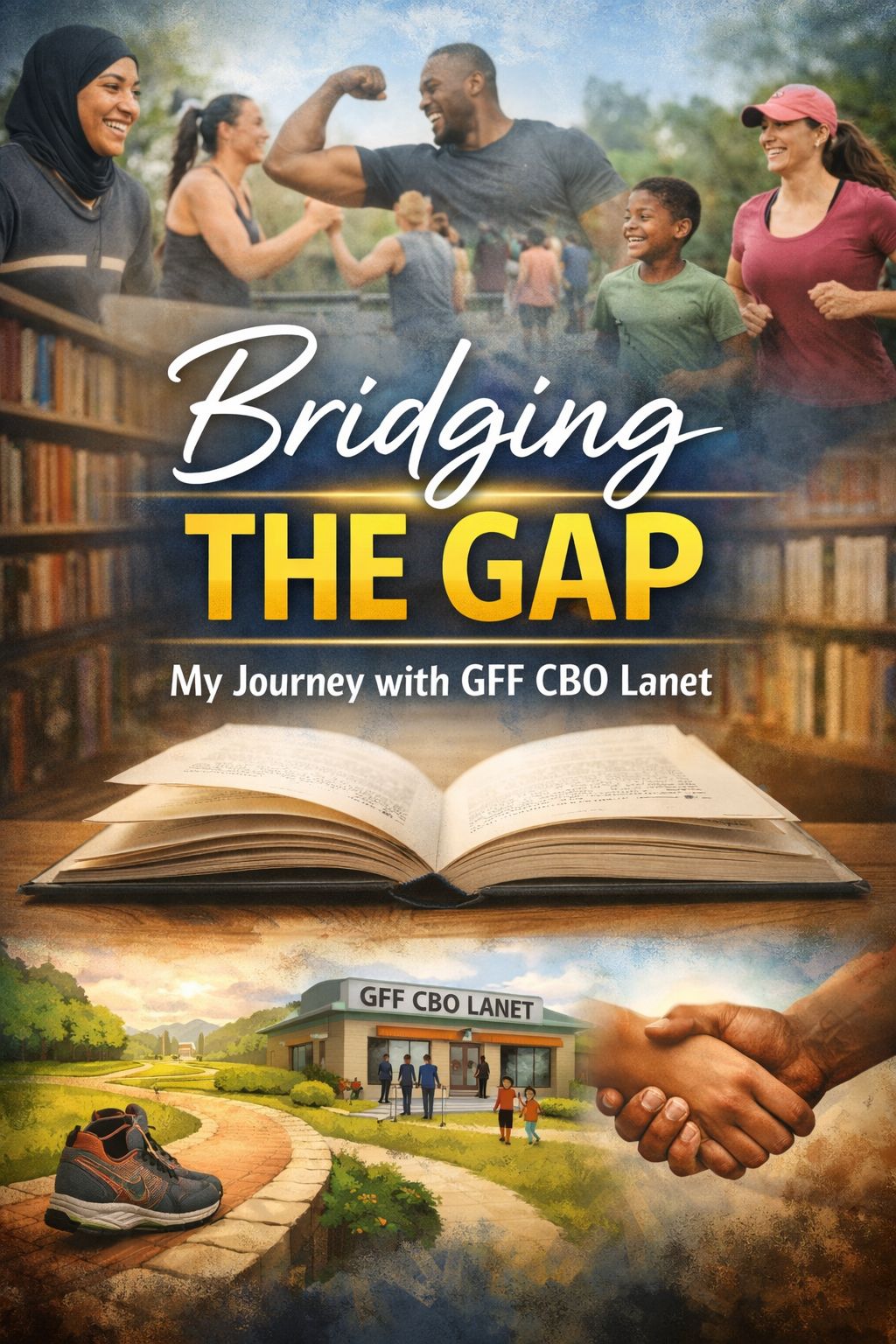

Bridging the Gap

Simon Njuguna Muchiri , Kenya Jan 27, 2026

Since the official opening of the Global Fast Fit CBO Lanet, I have met many people—each arriving with a different agenda, a different story, and a different goal. Some come seeking weight loss, others are drawn by sports, morning runs, or structured fitness routines. Yet despite these differences, there is one shared desire: to belong to a community.

For some, GFF CBO Lanet is more than just a fitness center. It is a safe space. A place where individuals feel seen, supported, and accepted. A place where parents feel comfortable bringing their children, knowing they are in an environment that promotes growth, discipline, and positivity. That sense of safety and trust is something we do not take lightly.

On my end, the journey has been equally transformative. Being part of this community has exposed me to opportunities beyond physical fitness. Through the book club within the center, I have found myself reading more, reflecting deeper, and gradually improving my communication skills. Conversations have become more intentional, and listening has become just as important as speaking.

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned is that people are different—and those differences matter. People think differently, react differently, and are motivated by different things. What works for one person may not work for another. This realization has taught me patience, empathy, and the importance of handling people as individuals rather than as a group.

Bridging the gap, therefore, is not just about fitness or programs. It’s about understanding. It’s about creating a space where different goals coexist, where diverse personalities are respected, and where growth happens both physically and mentally. At GFF CBO Lanet, the gap is bridged every day—through shared effort, open minds, and a community that continues to grow stronger together.

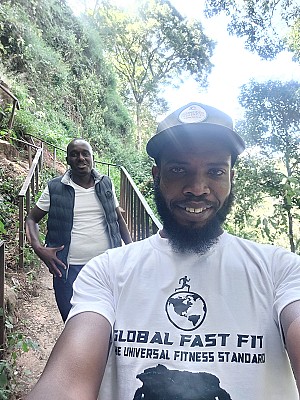

A Journey Beyond Borders: Our Global Fast Fit Experience in Uganda

Kelvin Njihia Kairu , Kenya Jan 25, 2026 2

The year 2026 began on a powerful note for us at Global Fast Fit. On 2nd January 2026, we proudly launched the Global Fast Fit Community Based Organisation in Nakuru, Kenya. Little did we know that this milestone would be immediately followed by an even bigger adventure — crossing borders to witness the launch of our sister club, COBAP Boxing Club, in Uganda.

Thanks to the sponsorship and support of Global Fast Fit, our journey officially began on 3rd January 2026.

Hitting the Road: The Journey Begins

Our travel team consisted of Meshack, our Nomads leader; Noxie, the Global Fast Fit Table Tennis Captain; and myself, travelling in the capacity of a Global Fast Fit Ambassador.

The plan was simple — catch a bus from Nairobi via Nakuru. Unfortunately, the bus never showed up. With no time to waste, we improvised and boarded a unit van, an imported vehicle transiting through Kenya to Uganda. Not the most comfortable option, but passion doesn’t wait for perfect conditions.

We departed at 11:00 pm. The van had limited leg space, and discomfort was unavoidable, but excitement overpowered everything. It was my first time travelling to a new country, and that alone kept my spirits high.

Border Lessons and Firsts

The journey flowed through Eldoret, Bungoma, and eventually Malaba, the Kenya–Uganda border. We arrived around 4:00 am, and the real adventure began.

Passport checks, vehicle clearance (since it was an imported van), and one important requirement — a Yellow Fever vaccine, which I had to take at the border. We also exchanged Kenyan currency for Ugandan shillings, immediately noticing the contrast: Kenya’s highest note is 1,000, while Uganda’s goes up to 50,000.

Paperwork done, we crossed over. I was officially in Uganda.

A Different World Across the Border

Almost immediately, Uganda felt different.

-

Heavy military and police presence every few kilometers

-

Traditional brew “chagaa” openly sold — illegal back home in Kenya

-

Fuel sold in roadside stalls, not just fuel stations

-

Lush greenery everywhere — forests, plantations, endless green

Uganda was visibly greener and more rural in feel. We were stopped once by military officers to verify our documents, a reminder that we were in unfamiliar territory.

Along the way, Sanyu Roberts, Head of COBAP Uganda, kept calling to check on our progress — a gesture that already made us feel welcome.

Jinja, the Nile, and Into Kampala

We passed through Jinja, crossed a heavily guarded bridge over the River Nile, and later reached Mukono, a sign that Kampala was close.

After 17 long hours on the road, hungry and exhausted but buzzing with excitement, we finally arrived in Kampala. The country was deep in general election campaign season — streets packed, energy high.

One thing that amazed me: despite heavy traffic police presence and seemingly chaotic bodaboda riding, I did not witness a single accident during my entire stay.

A Royal Welcome at COBAP

After arriving, Sanyu directed us to meet him. We already knew each other from boxing matches in Kenya, so the reunion was warm and familiar.

From there, we headed straight to COBAP Boxing Community — and what awaited us was nothing short of royal.

We were received with overwhelming love and excitement. Brendah “The Ring Beast,” Prince Kimera, Julius, Peter (their media in-charge), and the entire boxing team welcomed us like family.

The launch event featured:

-

Shadow boxing sessions

-

Speeches from important guests

-

The Guest of Honour, the Assistant Chairman of the Uganda Boxing Federation

Then came food — delicious chicken, meat, and local nut-based cuisines that absolutely hit the spot.

Meshack and Noxie later showcased table tennis, sparking huge interest among the boxers. It was beautiful to see sports crossing disciplines and borders.

Rest, Conversations, and Culture

By evening, fatigue finally caught up with us. We found a place to rest, then later chilled with Sanyu, who treated us as we shared long conversations about life, sports, and everything in between.

Uganda left a strong impression on me — peaceful, warm, and full of positive energy.

An Extended Stay & Deeper Connections

On Monday, 5th January, we were supposed to have a quick lunch — pizza and soda — and head back to Kenya. Saying goodbye already felt heavy.

But then came great news: Global Fast Fit decided to extend our stay. Joy doesn’t even begin to describe how we felt.

The next day, 6th January, we visited the historic Buganda Kingdom. Much of the history resonated with what I had learned in school — some inspiring, some painful, some violent — but all deeply important.

Later that day, we returned to COBAP to shoot videos and discuss Big Wave Tech, one of Global Fast Fit’s tech franchises. It was a productive and fulfilling day.

One Last Push: Training & Farewell

On 7th January, before heading back, we were given the privilege of training with the COBAP boxers. Let me tell you — it was tough. Brutal endurance, intense discipline, and pure grit. Massive respect to those athletes.

By evening, Sanyu escorted us to the bus station. This time, the bus was comfortable — but my heart was heavy.

Uganda had been incredibly kind to me:

-

The food

-

The positivity

-

The love

-

The people

Leaving felt unreal, but as we know, everything has an end.

Gratitude & A Perfect Start to the Year

Thank you Global Fast Fit for making this journey possible.

Thank you Sanyu, Brendah, Peter, Prince Kimera, and the entire COBAP family for the unforgettable warmth and hospitality.

Your kindness will forever remain in my heart.

We crossed back into Kenya, documents verified, and finally arrived in Nakuru safe and sound.

What a way to start the year.

What a journey.

What an experience.

FITNESS BEYOND THE GYM:HOW GFF IS BUILDING STRONGER COMMUNITIES.

Meshack Simiyu , Kenya Jan 23, 2026

Fitness Beyond the Gym: How GFF Is Building Stronger Communities

When people hear the word fitness, they often imagine weights, treadmills, and intense workouts inside four walls. At Global Fast Fit (GFF), we’ve learned that fitness is much bigger than that. It’s about people, purpose, and building communities that move—together.

Redefining What Fitness Means

At GFF, fitness goes beyond reps and routines. It’s about:

Creating safe spaces for people to be active

Using sport as a tool for connection

Making wellness accessible, not exclusive

From university clubs to community outreach, we believe fitness should meet people where they are, not the other way around.

Sport as a Bridge

One of the most powerful things we’ve seen is how sport brings people together. Through activities like table tennis, cycling, running, and functional fitness, GFF creates environments where:

Beginners feel welcome

Talent is discovered and nurtured

Discipline, teamwork, and confidence are built

You don’t need expensive equipment or elite status—just willingness to show up.

Community First, Always

GFF’s impact is strongest when we step into communities. Whether it’s visiting local clubs, working with schools, or organizing inclusive tournaments, the goal is the same:

use movement to inspire healthier lifestyles and stronger bonds.

Fitness becomes a shared experience—something that unites different ages, backgrounds, and skill levels.

Developing More Than Athletes

Yes, GFF develops fit individuals—but more importantly, it develops:

Leaders

Role models

Disciplined and resilient people

Through consistent training, mentorship, and exposure, participants grow not just physically, but mentally and socially.

The Bigger Vision

Our vision is simple but powerful:

A world where fitness is a community tool, not a privilege.

By blending wellness, sport, and outreach, GFF is proving that real impact doesn’t start in the gym—it starts with people.

When communities move together, they grow together.

And at Global Fast Fit, that’s the kind of strength we’re building—one session, one game, and one community at a time

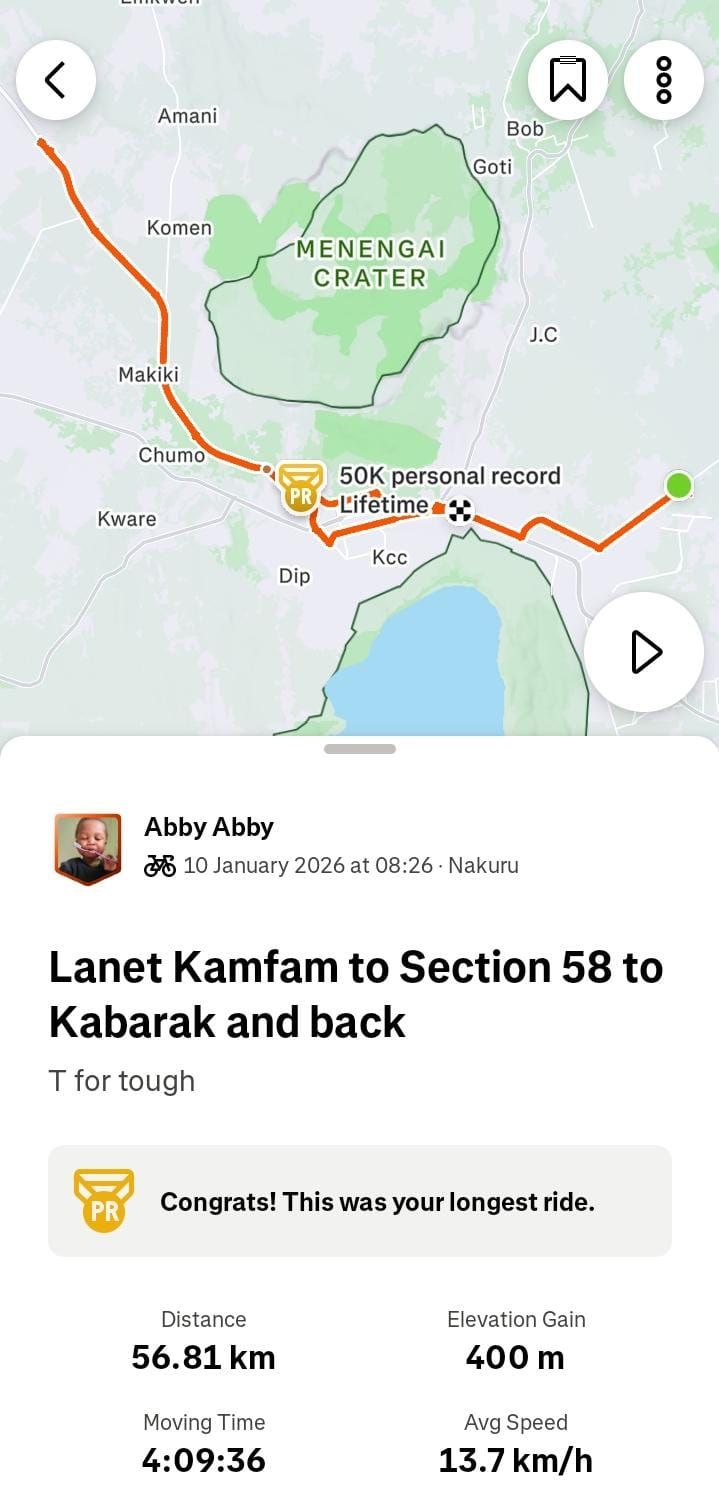

Little Miss Endurance

Abigael Rotich , Kenya Jan 23, 2026

I went for a bike ride and covered a total of 56.81 km in one day. My parents named me Abby, but you can call me Little Miss Endurance.

I love cycling. I think it is an excellent way to keep your weight in check, clear your mind, and build endurance. This ride proved all of that—and then some.

On that day, I covered 56.81 km, with a total elevation gain of 400 m, and a maximum elevation of 2,026 m. My average speed was 13.7 km/h, my fastest speed was 40.8 km/h, and my slowest was 4 km/h. My moving time was 4 hours, 9 minutes, and 36 seconds, not counting the several breaks I took along the way.

The experience was T for tough. I ended up with knee pain that lasted three days.

You may wonder how I ended up in this situation in the first place. Well, I saw an ad on TikTok—the social media platform. It said “Beginner-friendly bike ride.” I thought to myself, I am a beginner, I have a bike, I ride every day. This is the event for me. I showed up with a friend and was extremely pumped.

I did have a premonition, which I pushed deep down into my stomach, and instead chatted excitedly with the cyclists as they gathered into a big crowd outside the KFC Hyrax. We started the journey at a light pace, crossing town in single file, led by the cycling patron. It was breezy and calm—so calm that my mind drifted and I collided with the person in front of me while thinking about a pasta dinner I was going to make for my kids, using cheese that had overstayed in the fridge.

Around the 14 km mark, the ride started to get hard. We hit a steep incline. I was still pumped and pedaled on, determined. The incline had a brief flat section before turning into another steep climb. That’s when doubt started creeping in. By the time we reached the 28 km mark, after clearing the last steep incline, I regretted my choices that day. I really should not have come. I wondered if anyone would notice if I quietly turned back and went home—but the friend I had come with was right behind me and would not allow me to quit.

The next 6 km had softer inclines, and somehow, I made it to our destination. We took photos and ate a late lunch. By then, my knees were already starting to ache. Then we began the journey back. It took just 4 km before I had to stop by the side of the road, get off my bike, and lie flat on my back on the grass. Five other people joined me. My knees were killing me. We rested for about ten minutes and then, very reluctantly, got back on our bikes.

The worst part about the journey was this: even if you quit, you cannot leave your bike in the wilderness. You still have to ride back home. Thankfully, the return ride had more declines than inclines, and those were genuinely fun. Speed, wind, gravity—it almost made you forget the pain.

But let me say this clearly: they lied on that ad. That was not a beginner-friendly bike ride.

It was one of the toughest things I have ever done.

But I did it.

Because I can do anything.

Global Fast Fit Community Based Organisation: Redifining Health, Fitness And Connection In Nakuru County

Kelvin Njihia Kairu , Kenya Jan 23, 2026

On the 2nd of this year, something powerful was born in Nakuru County — the Global Fast Fit Community, a community-based organization created with one simple but bold mission: to transform community health through movement, mindset, and meaningful connection.

In a world where fitness is often limited to gyms and workouts, Global Fast Fit Community stands out as something far more holistic. It is not just a place to exercise — it is a hub, a movement, and a safe space where people of all ages and backgrounds come together to grow stronger physically, mentally, and socially.

More Than Fitness — A Lifestyle

What makes Global Fast Fit Community truly unique is its diversity of activities designed to cater to different interests, abilities, and fitness levels. Members are not boxed into one way of staying active. Instead, they are encouraged to explore movement in ways that feel exciting and sustainable.

Our community offers:

-

Physical training sessions focused on strength, endurance, and overall wellness

-

Boxing training, promoting discipline, confidence, and mental resilience

-

Cycling club, bringing riders together to explore, train, and build stamina

-

Running club, for those who love to push limits one step at a time

-

Walking club, because health should be inclusive and accessible to everyone

-

Table tennis, where beginners and experienced players can learn, train, and compete

-

Board games like chess and scrabble, sharpening the mind while building social bonds

This blend of physical activity and mental engagement makes Global Fast Fit Community one of the most unique health and wellness hubs in Nakuru County — and truly one of a kind.

Building Health Through Community

At the heart of Global Fast Fit Community is the belief that health thrives in community. People show up not just to train, but to belong. Friendships are formed during morning walks, confidence is built in boxing sessions, strategies are debated over chess boards, and laughter echoes around the table tennis courts.

This is a space where beginners are welcomed, growth is celebrated, and progress — no matter how small — matters.

A Vision for a Healthier Nakuru

Global Fast Fit Community is more than what it is today. It is a growing vision for a healthier, more active, and more connected Nakuru County. By making fitness engaging, inclusive, and fun, the organization is breaking barriers and redefining what community health looks like.

As the community continues to grow, one thing is clear: this is not just a fitness program — it’s a movement.

And this is only the beginning.

Medicine of the Future

Dr. James Muchiri , Kenya Jan 04, 2026

The medicine of the future will not smell like antiseptic or sound like monitors. It will sound like conversation. It will look like movement. It will feel suspiciously ordinary.

It will happen before anyone becomes a patient.

For a long time, medicine has been excellent at rescue. When the body collapses, we rush in with precision, protocols, and pharmaceuticals. This is heroic work. Necessary work. But rescue is not the same as care, and it is certainly not the same as prevention.

The future of medicine begins upstream.

It begins in how people move their bodies daily, not once a year on a hospital bed. It begins in whether communities feel seen, connected, and competent. It begins in whether health is something people do together or something done to them.

In that future, exercise is not a punishment for being overweight. It is a social ritual. A reason to gather at dawn. A shared language that needs no translation. Functional movement becomes medicine because it restores what modern life quietly erodes: strength, balance, confidence, agency.

Measurement still matters, but it changes character. Blood pressure, waist circumference, pulse, trends over time. Collected calmly, without drama. Not to label people as sick, but to notice when the body whispers before it screams.

The clinic walls soften. Some of the most important consultations happen over a chessboard, a table tennis rally, a shared walk, a cup of coffee. Cognitive health is not separated from physical health. Mental wellbeing is not outsourced to crisis moments. Belonging becomes a clinical intervention.

Technology plays a role, but not as spectacle. Artificial intelligence in the future of medicine is quiet, respectful, and useful. It lowers barriers instead of raising them. It helps people ask better questions about their own lives. It assists communities to organize, learn, and adapt without surrendering privacy or dignity. AI becomes a bicycle for health, not a replacement for human judgment.

Importantly, the medicine of the future is local before it is global. It is designed with communities, not dropped into them. It recognizes that behavior changes faster when people see themselves in the solution. When health feels like something owned, not prescribed.

Hospitals will still be there. Drugs will still save lives. Surgery will still be miraculous. But the center of gravity shifts.

The most powerful medicine of the future is time. Time spent moving. Time spent together. Time spent paying attention early. Time spent building systems that reward consistency instead of crisis.

The future doctor looks less like a gatekeeper and more like a systems designer. Someone who understands bodies, yes, but also environments, habits, incentives, and culture. Someone who knows that the strongest prescription is often not written on paper.

Medicine of the future does not wait for disease to announce itself.

It meets people where they are, helps them move forward together, and quietly makes illness less likely in the first place.

And when it works, almost no one notices.

Which is exactly the point.

Two Years Ago, A Champion Was Born

Kelvin Njihia Kairu , Kenya Dec 26, 2025

Today marks two years since I became a Global Fast Fit Pro Champion — a day that carries weight, meaning, and emotion for me.I remember that moment clearly: 30 push-ups. 30 squats. 30 plank leg lifts. A 500-meter run. All completed in 2 minutes and 55 seconds.

That record has since been broken — and that’s the beauty of growth. But I will always carry one truth with pride: I was the first person to ever complete it in under three minutes. That moment wasn’t just about speed or strength; it was about believing something was possible before anyone had proven it could be done.

That day, I met Global Fast Fit. And without knowing it, I stepped into a journey that would change my life. Two years later, I look back with deep gratitude. Global Fast Fit didn’t just build my fitness — it built me. It taught me discipline beyond the gym, responsibility beyond the stopwatch, and purpose beyond the title. From office work and report writing, to traveling, running marathons, organizing events, and meeting fitness influencers I once admired from afar — every experience shaped me.

There were moments of fatigue, doubt, and quiet struggle. Moments where growth demanded more than I thought I had. But step by step, task by task, I was becoming something stronger. This journey taught me that being a champion isn’t about holding records forever. It’s about opening doors, setting standards, and inspiring what comes next. Records will always be broken — but being first changes what people believe is possible.

Today, I don’t just celebrate a title.

I celebrate resilience.

I celebrate growth.

I celebrate two years of becoming.

I don’t take this journey for granted — not for a single moment.

Global Fast Fit didn’t just make me a champion.

It made me a trailblazer.

And the journey is far from over.

LESSONS FROM RUNNING WITH ANITA

Kelvin Njihia Kairu , Kenya Dec 23, 2025

Last weekend, I ran a 10km race with my six year old niece, Anita-and she taught me more about endurance than I expected.It was her first race of this kind, and while she did not run the entire distance non-stop, she ran an incredible 7 km and finished the race. That alone felt like a vicory

Her goal was simple and honest. She kept saying,"I dont want Esther and Abby to finish before me." Both of them had unknowningly become her motivation. There was no pressure, no pace targets- just a clear reason to keep moving forward.

There were moments Anita was tired. Moments when she slowed down, walked or needed encouragement. I learned quickly not to push her too hard. Instead, I listened. We pushed when she neede to, celebrated the small wins and kept going at her pace. The finish line mattered-so did the journey of getting there

At the end of the race, something special happened, Anita was awarded a medal from Joram, The Rurii Marathon organizer. Her face lit up with pride, and in that moment, every step she took made sense.

That day reminded me that progress is not about perfection. It is about effort, heart and knowing when to push-and when to rest. Anita may be six, but she already understands something most adults forget: finishing your own race is what truly matters

Login with Google

Login with Google

Signin with Apple

Signin with Apple